The Bible: Exploring Ecclesiastes

What’s in a name?

The book begins, “The words of the Teacher [Hebrew: Qoheleth]” (1:1). In the Greek Old Testament, the word translated “teacher” is Ekklesiastes, from which the English title for the book is derived. The Hebrew title is Qoheleth, which probably means “one who calls together an assembly” or “one who addresses an assembly.” Qoheleth is usually translated as “the Preacher” or “the Teacher.”

|

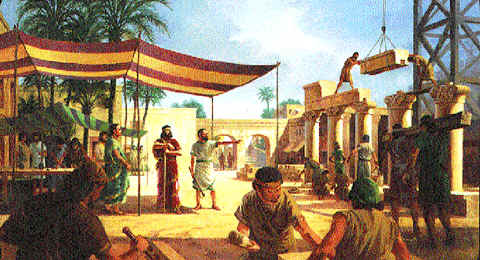

| Solomon boasted: “I undertook great projects: I built houses for myself and planted vineyards. I made gardens and parks and planted all kinds of fruit trees in them” (Ecclesiastes 2:4-5). Illustration by Ken Tunell |

Who was Qoheleth? Roy B. Zuck writes: “Some scholars argue that the anonymous author [Qoheleth] called himself ‘son of David, king in Jerusalem’ (1:1; cf. vv. 12, 16; 2:9) to give his book a ring of authority as having been written in the tradition of Solomonic wisdom. Others (including me), however, argue that the author is indeed Solomon” (“A Theology of the Wisdom Books and the Song of Songs,” in A Biblical Theology of the Old Testament, ed. Roy B. Zuck, p. 244).

Outline

After the first two chapters, Ecclesiastes does not have an obvious story flow. Rather, it is a collection of proverbs and short passages. However, some scholars believe that the book does have a discernible structure based on form rather than content. Although not vital to understanding the book, the outline presented below — based on Addison G. Wright’s observations regarding the occurrence of key phrases (“The Riddle of the Sphinx: The Structure of the Book of Qoheleth,” The Catholic Biblical Quarterly, vol. 30, 1968, pp. 313-334) — illustrates the formal details that the Hebrews delighted in when writing wisdom literature.

After a prologue concerning the profit of toil (1:1-11), the body of the book is then divided into two main parts. The first part (1:12–6:9) consists of eight sections (1:12-14; 1:15-17; 1:18–2:11; 2:12-17; 2:18-26; 3:1–4:6; 4:7-16; 5:1–6:9), each ending with a phrase such as “meaningless, a chasing after the wind.”

The second part of the body is divided into two sections. The first section (6:10–8:17) is further divided into four subsections (6:10–7:14; 7:15-24; 7:25-29; 8:1-17), each ending with a phrase such as “man cannot discover anything” or “this only have I found” [Hebrew: matsa’, translated “discover” elsewhere]. The second section is also divided into four subsections (9:1-12; 9:13–10:15; 10:16–11:2; 11:3-6), each ending with “no man knows” or a similar phrase.

The main part of the work concludes with a poem on youth and old age (11:7–12:8), which ends as the book began: “Everything is meaningless” (12:8; see 1:2). Finally, an epilogue (12:9-14) comments on the book.

How to read this book

Like the book of Proverbs, Ecclesiastes is wisdom literature. Ecclesiastes acknowledges the value of wisdom: “Wisdom, like an inheritance, is a good thing and benefits those who see the sun. Wisdom is a shelter as money is a shelter, but the advantage of knowledge is this: that wisdom preserves the life of its possessor” (7:11-12).

Ecclesiastes imparts wisdom in many areas of life, including law and justice: “When the sentence for a crime is not quickly carried out, the hearts of the people are filled with schemes to do wrong” (8:11).

But the special emphasis of Ecclesiastes is relating the limits of wisdom. First, wisdom is often ignored or forgotten: “The wise man, like the fool, will not be long remembered; in days to come both will be forgotten” (2:16). Solomon remembered when a poor man saved a city by his wisdom, yet soon this man’s deeds were forgotten. Solomon concludes: “‘Wisdom is better than strength.’ But the poor man’s wisdom is despised, and his words are no longer heeded…. Wisdom is better than weapons of war, but one sinner destroys much good” (9:16, 18).

Second, wisdom cannot eliminate chance misfortune: “The race is not to the swift or the battle to the strong, nor does food come to the wise or wealth to the brilliant or favor to the learned; but time and chance happen to them all” (9:11).

But the ultimate limit of wisdom is death: “Like the fool, the wise man too must die!” (2:16). Kenneth R.R. Gros Louis writes that the “Preacher…boils everything down to two great realities, to the essentials — death and chance” (“Ecclesiastes,” in Literary Interpretations of Biblical Narratives, ed. Kenneth R.R. Gros Louis, p. 278). Wisdom ends at death: “In the grave, where you are going, there is neither working nor planning nor knowledge nor wisdom” (9:10).

Learning about God

“What a heavy burden God has laid on men!” (1:13). Here is a key to this book. Solomon reflected on his material possessions, seeing them as empty and unable to provide meaning to his life. Many of his musings are somewhat cynical.

Admittedly, he acknowledges God’s sovereignty: “I know that everything God does will endure forever; nothing can be added to it and nothing taken from it” (3:14). Solomon also realizes that the proper attitude toward God is awe and respect: “Guard your steps when you go to the house of God…. Stand in awe of God” (5:1, 7).

Solomon even admits: “I know that it will go better with God-fearing men, who are reverent before God. Yet because the wicked do not fear God, it will not go well with them, and their days will not lengthen like a shadow” (8:12-13). But, despite all this, Solomon is wistful that God’s gift to humans is “to find satisfaction in his toilsome labor under the sun during the few days of life God has given him” (5:18).

Solomon accuses God: “God gives a man wealth, possessions and honor, so that he lacks nothing his heart desires, but God does not enable him to enjoy them, and a stranger enjoys them instead. This is meaningless, a grievous evil” (6:2). Those who cannot see beyond themselves, even if they had the wisdom of Solomon, are bound to have a distorted view of God.

Other topics

-

- Friendship: There is great value in finding a true friend: “Two are better than one, because they have a good return for their work: If one falls down, his friend can help him up. But pity the man who falls and has no one to help him up!” (4:9-10). And the best friend a person can have is a loving spouse. The best a man can enjoy in this life is to “enjoy life with your wife, whom you love, all the days of this meaningless life” (9:9).

Articles in “Exploring the Word of God: Books of Poetry and Wisdom” |

- Righteousness: The book of Proverbs emphasizes a general principle — the righteous prosper. Ecclesiastes concentrates on the exceptions to this principle: “In this meaningless life of mine I have seen both of these: a righteous man perishing in his righteousness, and a wicked man living long in his wickedness” (7:15). Solomon continues, “There is something else meaningless that occurs on earth: righteous men who get what the wicked deserve, and wicked men who get what the righteous deserve” (8:14).

- Work: Proverbs emphasizes that it is the diligent in life who prosper — laziness leads to poverty. Ecclesiastes, however, discusses work not as a means to an end, but as an end in itself. Solomon says, “My heart took delight in all my work” (2:10). He states emphatically, “A man can do nothing better than to eat and drink and find satisfaction in his work” (2:24).

Even though work brings some satisfaction, Solomon still considers it to be toil under the sun (2:11, 18) because its satisfaction is fleeting. Solomon bitterly observes: “A man may do his work with wisdom, knowledge and skill, and then he must leave all he owns to someone who has not worked for it. This too is meaningless and a great misfortune” (2:21).

What this book means for you

The Jews traditionally read Ecclesiastes at the Feast of Tabernacles. At this time of year, God’s people are commanded, “Eat the tithe of your grain, new wine and oil, and the firstborn of your herds and flocks in the presence of the Lord your God at the place he will choose as a dwelling for his Name” (Deuteronomy 14:23). The Feast of Tabernacles was a meaningful time to read Ecclesiastes, the book that tells us: “Nothing is better for a man under the sun than to eat and drink and be glad. Then joy will accompany him in his work all the days of the life God has given him under the sun” (8:15).

But the pleasures of eating and drinking ultimately satisfy no one. Several days of feasting help convince one that the physical does not satisfy. As Ecclesiastes emphasizes, death will shortly bring an end to pleasure anyway. Robert Gordis comments, “Koheleth’s insistence upon the enjoyment of life flowed from a tragic realization of the brevity of life” (Koheleth—The Man and His World, p. 93). At the Feast of Tabernacles, the Israelites were told to live in temporary accommodations (Leviticus 23:39-43). This illustrates the temporary nature of human beings.

Ecclesiastes gives a wealth of advice about how to make the most of this life. Yet an exasperated, despairing emptiness pervades the book. And, ironically, this is its greatest contribution. Ecclesiastes highlights the need we all have for something beyond anything this physical life can offer — to that which is made possible only by Jesus Christ (John 4:7-14).

Author: Jim Herst and Tim Finlay