Acts of the Apostles: In the Steps of the Apostle Paul

The message of salvation Paul carried to Europe 2,000 years ago can give us new hope for the future.

About A.D. 50 a spiritual crusade began in Greece that dramatically changed the tide of history. The apostle Paul landed on the European continent, armed with the gospel message given him by Jesus Christ. This project was so important in God’s purpose that he miraculously led Paul to Europe to teach the message of salvation, beginning in Macedonian Greece.

Luke, Paul’s traveling companion, explained that Paul had been prevented from preaching in certain areas of Greek-speaking Asia Minor, today western Turkey (Acts 16:6-8). “A vision appeared to Paul in the night,” Luke wrote. “A man of Macedonia stood and pleaded with him, saying, ‘Come over to Macedonia and help us” (Acts 16:9, New King James Version unless otherwise noted).

What did Paul teach that so revolutionized the religious and philosophical thinking of the European continent? Why should we, almost 2,000 years later in a very different world, be interested in that message?

In a letter to the church in the Greek city of Corinth, Paul boldly summarized that message. He wrote: “I determined not to know anything among you except Jesus Christ and Him crucified” (1 Corinthians 2:2). Today that might sound like a religious cliché or slogan. What does Christ crucified have to do with our daily life? It has to do with the most important part—salvation from evil and the gift of eternal life.

Paul announced Jesus of Nazareth as the Savior of the world and our personal Savior. He argued that Jesus’ suffering, death and resurrection mean that we can be saved from eternal death and have a part forever in the kingdom of God.

In Paul’s day those were revolutionary ideas. They still are. Then, as now, only a few accepted what Paul taught on God’s behalf. Only a few grasped the priceless opportunity that lay before them. Only a few responded to God’s calling.

Biblical odyssey

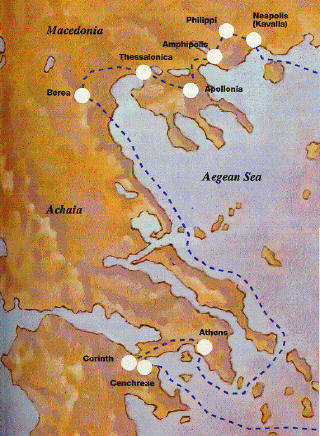

To proclaim this wonderful message in Europe, Paul landed on the northeastern coast of Greece, at Neapolis, today called Kavalla. It was a major Macedonian port of entry for travelers to Europe from the East.

After landing at Neapolis, Paul traveled to Philippi, some 10 miles northwest. It was in Philippi that he first preached the gospel of Christ in Europe (Acts 16:11-40).

Neapolis and Philippi were on the Via Egnatia (the Egnatian Way). It was the main Roman military road running east and west across Greece and the Balkan peninsula to the Adriatic coast. Travelers using this highway could then cross the Adriatic Sea by boat to Brundisium, on the Italian mainland. Here the Appian Way began, a road that led to Rome.

After teaching in Philippi, Paul made his way westward to Thessalonica (Acts 17:1) Paul proclaimed the gospel in this city for three weeks (verses 2-9). When a furor arose over his teaching, Paul had to leave. He turned south, off the Egnatian Way, stopping at Berea a short time (verses 10-14).

Some Bible scholars speculate Paul may have intended to go across Greece to the Adriatic Sea, sail to Italy and then take the Appian Way to Rome. But Paul did not then know that God was leading him to the southern Greek city of Corinth, where his major work was to occur.

With Paul in Athens

As Paul made his way south from Berea, he first visited Athens, somewhat east of Corinth. Thereby was created a tale of two cities—and two surprisingly opposite responses to God’s calling.

Athens had been one of the great cities of the world. The notion of democracy had begun and was nourished here. The city had been home to such men as Socrates, Plato and Aristotle. The Athens Paul saw was a major center of learning. Philosophy, literature, science and art flourished.

But in the main, Athens was basking in a glorious past. The Athens of Paul’s day had lost both its empire and wealth. Historians estimate the population was about 10,000. Athens remained a small town into modern times. But it is now a bustling metropolis of more than three million.

Athens was known as a center of superstition when Paul entered its streets. William Barclay writes in his commentary on Acts, “It was said that there were more statues of the gods in Athens than in all the rest of Greece put together and that in Athens it was easier to meet a god than a man” (page 130). It’s not surprising that Paul became distressed with the city’s impoverished spiritual condition. Luke writes that Paul’s “spirit was provoked within him when he saw that the city was given over to idols” (Acts 17:16).

Paul’s custom, as verse 2 indicates, was to first teach in the local synagogue. Here he would find Jewish worshipers and devout gentiles seeking to learn more about the God of Israel. It was in the synagogue that Paul began to teach in Athens (verse 17). Paul also discussed the Christian faith “in the marketplace daily with those who happened to be there” (same verse). The marketplace, called the Agora, was in the old town center. It was the forum and hub of public life.

Paul faces the philosophers

As Paul preached the word of God in this public place, he was confronted by Epicurean and Stoic philosophers. They asked sarcastically, “What does this babbler want to say?” (Acts 17:18). Others said that he was “a proclaimer of foreign gods,” because, as Luke says, “he preached to them Jesus and the resurrection” (verse 18).

These brilliant and educated Athenians didn’t understand the simple, though profound truth of God. Their intellectualism must have impressed Paul deeply. Later, he would write to the nearby Corinthian church, “The message of the cross is foolishness to those who are perishing” (1 Corinthians 1:18). The “Jews request a sign, and Greeks seek after wisdom” (verse 22).

Paul wasn’t interested in human philosophy, however. “We preach Christ crucified, to the Jews a stumbling block and to the Greeks foolishness,” he wrote, “but to those who are called, both Jews and Greeks, Christ the power of God and the wisdom of God” (verses 23-24).

It’s not surprising that the Epicureans and Stoics did not comprehend the gospel of Christ. The Epicureans believed the gods didn’t exist or weren’t involved with human affairs. To them, Paul’s God and Savior was just another foreign deity. The Stoics believed in reason as the principle by which humans should live. They relied on rational abilities and self-sufficiency. There was little place for a personal God in their thinking.

Questioned by the council

Paul’s preaching about repentance, the resurrection and salvation, as well as God’s judgment, must have seemed strange. In fact, it caused such a stir that the intelligentsia of Athens took him before the town council, the Areopagus, to explain himself.

The Athenian Areopagus was responsible for morals, culture, education and religion. The council also evaluated the competence of visiting lecturers to speak. To teach in their city, one needed the council’s official approval. The court met on the 377-foot hill called the Areopagus, or the Hill of the Greek god Ares (the Roman god Mars).

Imagine perhaps 30 council members, with power to decide whether Paul could teach about Christ. Before these noted thinkers and sophisticated philosophers stood the former rabbi, ready to explain the faith of Jesus Christ. The members of the Areopagus asked Paul, “May we know what this new doctrine is of which you speak? For you are bringing some strange things to our ears. Therefore we want to know what these things mean” (Acts 17:19-20).

How would Paul make the message of salvation seem sensible to these unbelievers? Paul didn’t begin his defense by referring to Jewish history or by quoting the Hebrew Scriptures. The Expositor’s Bible Commentary points out: “He knew it would be futile to refer to a history no one knew or argue from fulfillment of prophecy no one was interested in or quote from a book no one read or accepted as authoritative” (page 475).

Revealing the “Unknown God”

Paul referred to something the council could identify with. In the city, he had seen an altar with the inscription “To the Unknown God.” He used the inscription as a launching platform for his message. Paul told them, “Men of Athens, I perceive that in all things you are very religious” (Acts 17:22). “For as I was passing through and considering the objects of your worship,” he continued, “I even found an altar with this inscription: to the unknown god. Therefore, the One whom you worship without knowing, Him I proclaim to you” (verse 23).

As Paul further explained God’s purpose for humanity, he referred to what their own people of letters had said. “For in Him”—that is, in God —”we live and move and have our being, as also some of your own poets have said, ‘For we are also His offspring” (verse 28).

Paul the Roman CitizenPaul used his Roman citizenship to protect himself from mobs and false arrest. He also used it as a means to preach the gospel. In Philippi, Paul and Silas had been beaten and imprisoned overnight by the Roman authorities. When morning came, the town magistrates sent officers to set Paul and Silas free. But Paul said to them: “They have beaten us openly, uncondemned Romans, and have thrown us into prison…. Let them come themselves and get us out” (Acts 16:37). The magistrates “were afraid when they heard that they were Romans” (verse 38). Having violated the legal protection Roman citizenship afforded Paul, the magistrates came to free him and to apologize. According to The Expositor’s Bible Commentary: “A Roman citizen could travel anywhere within Roman territory under the protection of Rome. He was not subject to local legislation unless he consented…and he could appeal to be tried by Rome, not by local authorities, when in difficulty. As a citizen he owed allegiance directly to Rome, and Rome would protect him” (page 466). Paul on another occasion appealed to his Roman citizenship when the authorities wanted to beat him (Acts 22:25-29). He also appealed to have his case heard by Caesar’s judicial panel at Rome (Acts 25:10-11). The local Roman rulers, Festus and Agrippa, agreed (Acts 25:12; 26:32). Eventually, Paul arrived in Rome—the international capital of the world—and preached the gospel for two years because of this appeal (Acts 28:30-31). |

Paul told the council that humans “should seek the Lord, in the hope that they might grope for Him and find Him” (verse 27).

Paul preached the same message of conversion to the Athenian town council as he might have to you and me. He told these magistrates that God “is not far from each one of us” (same verse).

This God “now commands all men everywhere to repent,” said Paul to the council, “because He has appointed a day on which He will judge the world in righteousness by the Man whom He has ordained” (verses 30-31).

The council members’ response was either polite disinterest or ridicule. Luke tells us when “they heard of the resurrection of the dead, some mocked, while others said, ‘We will hear you again on this matter’” (verse 32).

Yes, some council members were interested in hearingabout Jesus. The Athenians loved to discuss philosophy and religion. Luke notes that “all the Athenians and the foreigners who were there spent their time in nothing else but either to tell or to hear some new thing” (verse 21).

However, God’s truth is not something we only talk about. It is something we put into practice. The knowledge of Christ demands action. This includes changing our lives.

A few Athenians did respond to Paul’s preaching. Even one of the council members, Dionysius, was willing to act on Paul’s message. He believed the gospel, as did an influential woman, Damaris, and a few others (verse 34).

Beyond these, almost no one was responding to God’s calling in this great intellectual and idolatrous city. Though a little spiritual fruit was borne, there is no further mention of the city in Scripture. As the Areopagus had not approved Paul’s right to teach, Paul had a choice. He could wait in Athens until the council decided yea or nay. Or he could move on to another city where his message might receive a better hearing.

With Paul in Corinth

Commentaries on Acts of the Apostles |

Paul chose to leave Athens. His next destination was the commercial city of Corinth. As usual, Paul entered the synagogue every Sabbath where he testified that “Jesus is the Christ” (Acts 18:4-5).

The Corinth of Paul’s day was a more prominent city than Athens. Because of its strategic location between the Greek mainland and the Peloponnesian peninsula, it was a prosperous city-state and commercial center. Corinth’s population was probably more than 200,000, or at least 20 times that of Athens. Today, the two cities have switched roles in size and vigor. Modern Athens is a huge city; Corinth is a small town with a population of about 20,000.

Ancient Corinth was built on the north side of the Acrocorinth, an acropolis rising precipitously to almost 2,000 feet. The hill was home to a temple of Aphrodite, which stood on the highest point of the Acrocorinth. In the temple’s flourishing days it had a thousand priestesses of Aphrodite who were sacred prostitutes. In the evening these prostitutes came down to the city streets.

Ancient Corinth was known as the Sin City of Greece. The Greeks had an expression, “to play the Corinthian.” It referred to people who lived a life of debauchery. This pleasure-mad life-style plagued many of the Corinthian believers even after conversion. They struggled to put their immoral life behind them. Because of their spiritual problems, Paul had to write a strong corrective letter to the Corinthians a few years after his visit.

Paul’s words were to the point: “Neither fornicators, nor idolaters, nor adulterers, nor homosexuals, nor sodomites, nor thieves, nor covetous, nor drunkards, nor revilers, nor extortioners will inherit the kingdom of God.And such were some of you” (1 Corinthians 6:9-11, emphasis ours).

A tale of two cities

The Corinthian converts sometimes gave in to their fleshly weaknesses. However, they had committed themselves to a new way of life and showed faith in Christ. That is what’s so unusual about their response to Christ. We might imagine the worldly and morally corrupt Corinthians would show little interest in a Jewish carpenter, especially one who preached a hard-to-follow spiritual morality.

On the other hand, the Athenians were interested in moral questions, in philosophy and in religion. We might have expected them to be more willing to listen to God’s truth. In this ironic tale of two different cities, the opposite proved true. Unlike the citizens of Athens, many Corinthians listened to Paul’s message, believed it and were baptized.

The apostle Paul himself had not known what to make of the Corinthians’ unexpected interest in God’s message. While teaching in the city, Paul had a vision from God. A voice told him: “Do not be afraid, but speak, and do not keep silent; for I am with you, and no one will attack you to hurt you; for I have many people in this city” (Acts 18:9-10).

In this most worldly of cities, the spiritual harvest was so large that Paul taught at Corinth and ministered to the believers for 18 months (verse 11). While a few influential people may have been converted in Corinth, most were average folks or the downtrodden.

Paul would explain: “Brothers, think of what you were when you were called. Not many of you were wise by human standards; not many were influential; not many were of noble birth. But God chose…the weak things of the world to shame the strong…so that no one may boast before him” (1 Corinthians 1:26-29, NIV).

Paul, Apostle to the GentilesGod chose an individual well suited to the task of proclaiming the gospel message and establishing churches in Europe. He who preached Christ’s gospel “can justly be called the first European—the educated rabbi Paul, who was thoroughly at home with Greek literature and philosophic thought… and who was also a Roman citizen” (Eerdmans’ Handbook to the Bible, page 559). Paul campaigned mostly in major cities, selecting trading centers from which the message of Christ could be spread far and wide. Those cities—such as Thessalonica or Corinth—also had Jewish colonies and synagogues. Paul employed a simple strategy in spreading the gospel of Jesus Christ in Greece, as he did everywhere he preached. He usually visited the local synagogue where Jews and devout gentiles gathered on the Sabbath day, and where the Holy Scriptures, the Christian Old Testament, were read (Acts 17:1-2). In the local synagogue, Paul, a former rabbinical teacher, could proclaim Jesus as the Messiah to all who gathered for worship services. For this reason the apostle’s work would usually not begin until the Sabbath, when he went to the Jewish meeting place. |

What was it Paul taught these Corinthians that so many changed their way of life so dramatically? It was “Jesus Christ and Him crucified” (1 Corinthians 2:2).

That story of Christ crucified is as important to us as it was to the Jews, Greeks and Romans of the first century. The heart of this story’s message is that all humans have sinned.

We all need the atoning sacrifice of Jesus. It is only through Jesus Christ, said Paul (Acts 13:38), that we can have forgiveness and eternal life.

Paul told them that Jesus’ sacrifice should inspire human beings to make a lifelong commitment to God. Paul wrote that Christ “died for all, that those who live should live no longer for themselves, but for Him who died for them and rose again” (2 Corinthians 5:15).

Yes, Christ died, but he was also resurrected. That’s the good news story (1 Corinthians 15:1-4). Our salvation—the hope of our own resurrection —depends on Jesus’ resurrection (verses 12-26).

Paul’s message of salvation was much more than theology. He called on his hearers and readers to change the way they lived and viewed life. To bring their “every thought into captivity to the obedience of Christ” (2 Corinthians 10:5). Paul preached then—and he does so to us through his writings—that we humans “should repent, turn to God, and do works befitting repentance” (Acts 26:20).

Paul said that through Christ’s earthly ministry and living presence we can experience the spiritual power of God in our lives. He wrote the Philippians from prison, saying, “I can do all things through Christ who strengthens me” (Philippians 4:13). Through the power of God in us, we can belief in Christ as our Savior. The result is our salvation—a gift from God.

That is the message Paul took to the Greeks almost 2,000 years ago. That is the message we can read in Paul’s writings and in Luke’s account of Paul’s life. That is the message we announce—a message that can change our lives and give us hope for eternal life.

Author: Paul Kroll and Ronald Kelly