Church history: The Great Disappointment

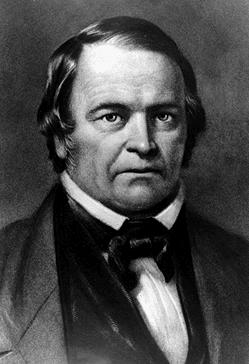

On October 22, 1844, as many as 100,000 Christians gathered on hillsides, in meeting places and in meadows. They were breathlessly and joyously expecting the return of their Lord and Savior, Jesus Christ. The crowds had assembled because of the prophetic claim of an upstate New York farmer and Baptist layman named William Miller (1782-1849). He was certain from his studies of the Bible that Jesus Christ was going to return on that day.

The prophesied return date had arrived. The waiting crowds, gathered at various places, mainly throughout the Northeast United States, peered expectantly upward as the hours slipped away. Anxiety grew as nightfall descended. Then the midnight hour tolled and still Christ had not returned. People became ever more restless. Through the wee hours of darkness, the dejected and stunned crowds began to disperse. When the daylight of Oct. 23 arrived, it was clear that Christ was not going to return as expected.

The prophesied return date had arrived. The waiting crowds, gathered at various places, mainly throughout the Northeast United States, peered expectantly upward as the hours slipped away. Anxiety grew as nightfall descended. Then the midnight hour tolled and still Christ had not returned. People became ever more restless. Through the wee hours of darkness, the dejected and stunned crowds began to disperse. When the daylight of Oct. 23 arrived, it was clear that Christ was not going to return as expected.

Failed prophecy and its aftermath

This dashed hope came to be known as “The Great Disappointment.” In his book When Time Shall Be No More, historian Paul Boyer offers an example of the deep despondency suffered by the Millerites. In the words of one tragically disappointed believer: “Our fondest hopes and expectations were blasted, and such a spirit of weeping came over us as I never experienced before…. We wept, and wept, till the day dawned” (page 81).

When Jesus did not return as expected, many who had hopefully waited for the return of their Savior threw off their faith completely. Some refused to give up their hope and eventually replaced one delusion with another. They would claim that Christ must have come invisibly in 1844, moving into the Holy of Holies in heaven to begin his “investigative judgment” of Christian lives.

Many simply returned to the churches out of which they had come, no doubt confused, distraught and embarrassed to have accepted something that was revealed to have been an empty fantasy. Miller, having renounced his prophecy studies after the Great Disappointment, died in 1849. Any remaining followers split up over differences of belief and doctrine. Ultimately, a variety of groups arose from the ashes of the Millerite camp, including the Jehovah’s Witnesses and Seventh-day Adventists.

Actually, the October 1844 debacle was the second great disappointment for followers of Miller’s chronology and prophecy blueprint. He had previously announced that the coming of Jesus Christ would occur in about the year 1843. The year came and went without Christ’s return. Miller’s prophetic claim had failed and disappointed many people.

Then someone pointed out that he had neglected to take into account the transition from B.C. to A.D., so that his calculations were one year off. Miller then moved the expected return of Jesus forward by one year, this time to Oct. 22, 1844. But the great disappointment happened once again to the thousands of followers who had given away their possessions and waited in expectant belief — for nothing.

William Miller, as all Christians do, yearned for the coming of God’s kingdom. However, this yearning was translated by him into a misguided belief that Christ’s return would occur in his time on a specific date. Miller thought he had discovered in the Bible certain prophecies, which if rationally studied, could provide him with a certain date for Jesus’ return. His study and calculations of various prophecies, such as the 70 weeks prophecy of Daniel 9 and the 2300 days of chapter 8, brought him, he believed, to Oct. 22 as the date for Christ’s return.

American prophetic streak

Prophetic beliefs such as Miller’s are strongly entrenched among some Christians and in American popular religion. The Millerite movement of the 1830s and 1840s was not an isolated event. As Miller and other leaders of his movement crisscrossed the northern states, they found a ready audience of people who held to various prophetic ideas about how and when Jesus would return.

The Millerite phenomenon is not an isolated movement, but grew up in a Premillenialist culture popular with many Christians. Many tens of thousands of Christians living at the time — average people — were eager to follow Miller’s belief or some other prophetic scheme. As Boyer observes, quoting from David Rowe, a commentator on the Millerite experience: “Millerites are not fascinating because they were so different from everyone else but because they were so like their neighbors” (When Time Shall Be No More, page 82).

The excitement in speculative prophecy that characterized the Millerites has continued through the 19th and 20th century, and into our time, especially under a different mode of interpretive prophecy identified as Dispensationalism. This movement began through the work of John Nelson Darby (1800-1882).

Though most prophecy buffs of a Dispensationalist persuasion have avoided setting exact dates for Jesus’ return, they nonetheless continue to use Bible prophecy as a blueprint for their views of the end time. Usually, they maintain that his coming is imminent — in our generation. They claim the next dispensation of God’s dealing with humanity will begin with the rapture — when the Christian saints are supposedly taken to heaven while the rest of humanity is left behind.

‘Imminent return’ the watch phrase

To Dispensationalists, the signs of the times are always with us. While date-setting is usually avoided, Christians are told that they must be ready because the rapture could occur at any moment. The time of the end is always right now, even though we may not know the precise date. Many fundamentalists, evangelicals — and other Christians — still believe that biblical prophecy is meant to be interpreted in such an apocalyptical and speculative way. If rightly interpreted, they believe, biblical prophecy can tell us what will happen in the near future — in our lifetime.

But as with William Miller’s failed calculations, all this speculation about the end of the age is the invention of often brilliant, but confused minds. Christians would do well to remember the Great Disappointment of Oct. 22, 1844. Miller’s prophecy construct seemed like a logical and biblically based creation, but proved to be nothing more than a mirage.

Author: Paul Kroll