The Torah: No Contest – Why the Argument Over Genesis?

One doesn’t have to be religious to know that a great controversy surrounds the first chapter in the Bible. The way it is written seems to suggest that the whole universe, including the Earth and all life, was made by God in just six days. Some Protestant Christians insist on taking this literally. Genealogies in succeeding chapters are then supposed to lead us to the conclusion that all this happened 10,000 years ago, more or less.

This creationist viewpoint has been forcefully asserted, especially during the latter part of the 20th century, and the media have been very effective in reporting it. There is, therefore, a general sense among the biblically illiterate general public (and even many Christians) that the majority of Christians have always held such a view. This is not the case.

This creationist viewpoint has been forcefully asserted, especially during the latter part of the 20th century, and the media have been very effective in reporting it. There is, therefore, a general sense among the biblically illiterate general public (and even many Christians) that the majority of Christians have always held such a view. This is not the case.

According to Conrad Hyers, author of The Meaning of Creation, allegorical interpretations of Genesis 1 were common in the Patristic (early) and Medieval Church, whereas Protestant Reformers leaned toward a literal approach. Martin Luther, for example, criticized Augustine (A.D. 354–430) for Augustine’s allegorical interpretation of the six days of

Creation.

Today, there are numerous religious books about the Genesis Creation written by evangelical or fundamentalist scientists who ridicule evolution and rewrite geological history, meanwhile demanding that the Genesis accounts can be interpreted only and wholly literally. Wedded to a particular paradigm, they fail to consider carefully what type of literature it is, why it was written, who the audience was, and what were the historical/cultural and religious settings in which Genesis was written.

The fact is, a literal interpretation of Genesis 1 has nothing to do with science, and it is poor theology to suggest it does. “Young earth” creationists have overlooked the first principles of exegesis. Exegesis is the systematic study of Scripture to discover the original, intended meaning.

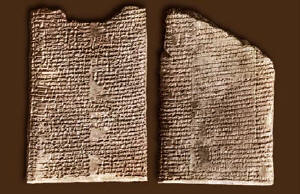

| Translation of the fifth tablet of the Enuma Elish |

| Compare the order of deities with that of the celestial bodies in Genesis 1:16, in which the order is deliberately reversed.

|

When exegesis is done properly, Genesis 1 is seen for what it is — a literary masterpiece, an intelligent, carefully crafted assertion of monotheism against polytheism (many gods), a matter of great significance for the people who were alive when Genesis 1 was written. Many chapters of the Old Testament record how the people of Israel preferred to “go whoring after other gods” than follow the one true God.

Cosmogony or cosmology?

Moses wrote the Creation account as a cosmogony that was intended to counter the well-known cosmogonies of the pagans.1

A cosmogony is a story of the genesis or development of the universe and the creation of the world, whereas cosmology is strictly a formal branch of philosophy dealing with the origin and general structure of the universe. We know what the commonest pagan cosmogonies were because they are preserved in cuneiform script on clay tablets.

The best-known cosmogony, the famous Babylonian creation epic known as the Enuma Elish, itself based on earlier, pre-Mosaic versions, was written some time after Moses. When you read a translation of it (see box), you can see what the Israelites were up against. It

describes a struggle between cosmic order and cosmic chaos. There are great sea monsters, and the chief divinities, in order of pre-eminence, are the stars, the moon, and the sun. Other gods abound in the cosmogonies — gods of darkness, water, vegetation, various animals, and so on.

| “Exegesis is the systematic study of Scripture to discover the original, intended meaning. When this task is done properly, Genesis 1 is seen for what it is — a careful, intelligent, extraordinarily crafted assertion of monotheism against polytheism. It is stunning in its brevity and effectiveness.” |

The Enuma Elish and earlier cosmogonies help us understand why the Genesis account is written as it is. As one archaeologist has written, Genesis freely uses the metaphors and symbolism drawn from a common cultural pool to assert its own theology about God.

In the beginning…

Let’s now look at the structure of Genesis 1 to see how this works (for this you might want to consult a Bible). It starts out with a summary statement: “In the beginning God created the heavens and the earth [the universe].”

Most of the verses in the chapter hinge upon the next statement, in verse 2: “The earth was without form and void, and darkness was upon the face of the deep.” The following verses explain how God respectively structured and “filled” the conditions of formlessness and emptiness. The six days are arranged in two parallel sets of three (noted as early as Augustine in his City of God), such that what is created on days four through six populates the appropriate realm structured in days one through three.

| Problem | Preparation | Population |

| Verse 2 | Days 1-3 | Days 4-6 |

| darkness | day 1a – creation of light (day) day 1b – separation from darkness (night) | day 4a – creation of sun day 4b – creation of moon and stars |

| watery abyss | day 2a – creation of firmament (sky) day 2b – separation of waters above from waters below | day 5a – creation of birds days 5b – creation of fish |

| formless earth | day 3a – separation of earth from sea day 3b – creation of vegetation | day 6a – creation of land animals day 6b – creation of humanity |

| without form and void | tohu (formlessness) is formed | bohu (the void) is filled |

The point of this symmetry in Genesis 1 is that the form of the presentation is at least as important as the content. With this perspective, it is clear that the structural framework is artificial and therefore was never intended by the author to be taken literally as a seven-day

historical account (with God resting on the seventh day). The fact of God’s creative authority over everything is certainly intended literally, but the seven-day framework is just that — a framework.

As Victor Hamilton in his 1990 commentary on Genesis 1 wrote, “A literary reading of Genesis 1…understands ‘day’ not as a chronological account of how many hours God invested in his creating project, but as an analogy of God’s creative activity. God reveals himself to his people in a medium [a seven-day week] with which they can identify and which they can

comprehend.”

How the ancients saw the world

We need to understand that, for most peoples of the ancient world, all the various regions of nature were divine. There were sky gods, earth gods and water gods, gods of light and darkness, rivers and vegetation, animals and fertility. Everywhere the ancients turned, there were

divinities to be petitioned, appeased, or pacified.

Each day of Creation in Genesis 1 takes on two principal categories of divinity and declares that these are not gods at all but creations of the one and only true God. This includes humans, none of whom — not even kings or pharaohs — are to be worshipped as gods.2

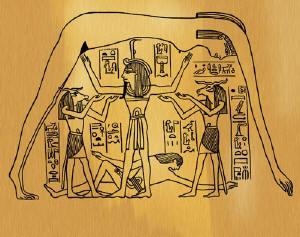

|

| From the Egyptian book of the dead, the god Shu separates Nut (the sky) from Geb (the earth). |

Hebrew monotheism (one God) was a unique and hard-won faith. The temptations of idolatry and syncretism (blended religion) were everywhere. Later in history, it came to be understood just how liberating was the concept of monotheism. From time immemorial, superstitious people have

attributed natural phenomena, or calamities like earthquakes, volcanic eruptions and tsunamis, to gods who were beyond understanding (except by a priestly elite) and had to be appeased and not questioned. Genesis 1, on the other hand, asserts that there are no gods but God and that his creation is comprehensible and amenable to investigation. This perspective made possible the scientific study of nature.

Verse 16 of Genesis 1, when understood, is amusing. As an intentional put-down, it deliberately reverses the order of the chief deities of a well-known cosmogony. The sun — called the “greater light” to avoid using the only available Semitic names for the sun, which were names of deities — comes first, then the moon, the “lesser light.” The stars — the highest

deities — are barely mentioned in a throw-away line: “He made the stars also”! Not only that, Genesis 1 makes it plain that they are not to be worshipped; they were made to serve — daily, seasonally, and calendrically. And none is accorded astrological significance.

You see the contrast? In this chapter, God overcomes darkness, makes order out of chaos, and even makes the great sea creatures, which, as it happens, are not monstrous. The impressive orderliness of Genesis 1 and its patterned structure are a deliberate response to pagan

mythologies. The Hebrew God has no competitor and there is no cosmic battle going on. Everything is under control.

No contest

Genesis 1 is not at odds with modern geology and biological science. This is not an issue here. To insist that it is does violence both to Scripture and to science. As Victor Hamilton wrote, “This is a word from God addressed to a group of people who are surrounded by nations whose cosmology is informed by polytheism and the mythology that flows out of that polytheism. Much in Genesis 1 is patently anti-pagan…. The writer’s concerns were theological.”

For more information, see our three interviews with Dr. Gordon.

Both Henri Blocher and Rick Watts (see Further Reading) have highlighted the similarities and differences between the Genesis account and some themes apparent in Egyptian cosmogonies (something relatively few scholars have attempted). In short, Genesis 1 is a corrective against

polytheistic concepts encountered by the Israelites in their old land as well as in their new.

Dennis Gordon is a biologist in a government research organization in New Zealand and an Associate Member of the U.K.-based Society of Ordained Scientists. He obtained his PhD in 1973 (Dalhousie University, Canada), was baptized in the same year, and was

ordained in 1980.

Further reading

- Blocher, H., and R. Preston. In the Beginning: The Opening Chapters of Genesis. InterVarsity Press, 1984. 240 pages.

- Gibson, J.C. Genesis (volume 1). The Daily Bible Study Series. Westminster John Knox, 1981. 228 pages.

- Hamilton, V.P. The Book of Genesis: Chapters 1–17. The New International Commentary on the Old Testament. Eerdmans, 1990. 522 pages.

- Hyers, M.C. The Meaning of Creation: Genesis and Modern Science. Westminster John Knox, 1984. 216 pages.

- Watts, R. “Making Sense of Genesis 1.” Stimulus 12(4) (2004): 2–12.

www.stimulus.org.nz/index_files/Stim12_4RikkWatts.pdf.

Endnotes

1 Moses is taken to be the author of Genesis. As Henri Blocher, Professor of Theology at Wheaton College, Illinois, has written: “We stand…with the contemporary specialists who

maintain the traditional positions, those suggested by the Bible itself, which associate Genesis with the work of Israel’s most powerful thinker, ‘our Teacher,’ as the Jews call him, Moses.” And for good reason — his training in Egypt and his later pastoral life uniquely equipped him intellectually and spiritually, as one who was “instructed in all the wisdom of the Egyptians”

(Acts 7: 22) and who was filled with the Spirit of wisdom, which he later passed on to Joshua (Deuteronomy 34:9)

2 All humans, men and women equally, not just pharaohs and kings, are said to be made in the likeness of God, with the royal prerogative of rulership (properly, stewardship) over the

earth. This equality of men and women, extended to common folk, was revolutionary teaching!

Bible photo: iStockphoto.com

Illustration: ResonanceImages

void and empty, so what was formless was now formed. So that solves

that problem on the first three days.

What God then does in the second set of three days is solve the second

problem, of emptiness, and then God populates each of the realms that he

structured on the first three days. So on the first day we have the separation

of day from night, and what do we populate that realm with, if not the sun and

the moon and the stars? Then on day two we separate the waters above from the

waters below, and what do we see populating those realms, but the birds in the

upper atmosphere and the fish in the sea? Then on day three, the land animals

and human beings populating that realm that was formed on day three, and that

solves the problem of emptiness.

And so in that account, Moses is showing that the God of Israel is the

God who is greater than all forces and life and everything. But incidentally,

as you’ve pointed out, on each of those days Moses is taking elements that the

pagans worship and showing that things that the pagans worship were, in fact,

creations of the one true God. There’s a definite structure in there. We see

that six plus one or, in fact, three plus three plus one framework is just

that, it’s a structural framework on which to hang that story.

JMF: So, in Genesis,

the God of Israel is actually creating, structuring, and manipulating to his

own pleasure everything that the pagan cosmogonies are actually holding up as

gods — the still water, the canopy of the sky, down to the crocodiles and

everything that Egyptians worshiped, the rivers, the sweet waters, and the

non-sweet waters, and all those things that become the gods of the ancient

cosmogonies. It’s really a very theological statement, a declaration as opposed

to some kind of scientific day-by-day “here’s how God created”…

DG: [A scientific

description] is not at all the point of it. The issue is polytheism, many gods,

versus monotheism or one God. That’s the issue. That was the issue for Israel,

because when they were to come into the promised land and beyond. So many times

we read in the Old Testament how the prophets lamented that the people of God

kept whoring after other gods. It seems that they constantly had to be reminded

that there was one God, the one true God of Israel, not a whole host of gods. It

was an issue, a critical issue for them.

In Genesis 1 God is establishing from the outset that the God of Israel

is the Creator God. That’s the issue, that’s the context. Again, the Exodus is

the context in which we read Genesis. And then, in the first 11 chapters and

beyond, what else does Moses do? Well, there are lots of genealogies. The

genealogies connect Israel with Adam, to show that they have an origination.

And then Genesis 12-50, the larger part of the book of Genesis, deals

with the patriarchs Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob, and then this story of Joseph

and the 12 tribes of Israel, and that then takes you up to the Exodus story. That’s

what Moses is doing – he is making that connection from the beginning to the

end. But again, it’s set in the context of the Exodus. God is a God who is

bringing about redemption and salvation, and he’s the Creator God, what is

more.

JMF: So you’ve got a

declaration of who God is, you’ve got then a declaration of who Israel is in

light of who God is, and that is all leading, of course, to the matrix from

which the Messiah would come, and we move into John 1:1 and we find that behind

all this all along, the Son of God himself is this Messiah who emerges out of

Israel, who God formed from the beginning, and the whole story adheres together

in a way that you really can’t see if you’re focused on trying to make Genesis

1 a science book.

DG: Precisely. And it

does a great disservice to Genesis to do that, because we’re bringing in our

own 21st-century issues and mindset and orientation, and imposing it in the Scripture

or context where it doesn’t belong. So, in fact, a young earth and insistence

on a literal day-by-day interpretation does violence both to Scripture and to

science. But in any case, going back to this whole issue of addressing

monotheism versus polytheism in Genesis 1, in many ways it’s actually quite

amusing.

The Mesopotamian cosmogonies held the stars or the deities associated

with the stars to be the highest of all deities next to the moon and next to

the sun. On day four in Genesis 1:16 we have this line, “And God created the greater

light to rule by day and the lesser light to rule by night, and he made the

stars too.” When you understand what’s going on, that’s actually a very amusing

verse because it deliberately reverses the importance of those divinities

that’s in the pagan gods’ cosmologies. Instead of the stars being the most

important deities in this pantheon, he presented them in a throw-away line, oh

and God made the stars, too…

JMF: An afterthought

(both laughing).

DG: But we may also

ask, why does Moses use this curious expression, the greater light and the

lesser light?

JMF: Well, let’s hold

that thought and we’ll be back with part two, and we’ll carry on from there.

DG: Okay.

JMF: Thanks.

DG: You’re welcome.

Author: Dennis P. Gordon, 2007

He [Marduk] made the stations for the great gods; The stars, their images, as the stars of the Zodiac, he fixed. He ordained the year and into sections he divided it; For the twelve months he fixed three stars. The Moon-god he caused to shine forth, the night he entrusted to him. He appointed him, a being of the night, to determine the days; Every month without ceasing with the crown he covered him, saying: “At the beginning of the month, when thou shinest upon the land, Thou commandest the horns to determine six days, And on the seventh day to divide the crown.” When the Sun-god on the foundation of heaven… thee,…[tablet here damaged]

He [Marduk] made the stations for the great gods; The stars, their images, as the stars of the Zodiac, he fixed. He ordained the year and into sections he divided it; For the twelve months he fixed three stars. The Moon-god he caused to shine forth, the night he entrusted to him. He appointed him, a being of the night, to determine the days; Every month without ceasing with the crown he covered him, saying: “At the beginning of the month, when thou shinest upon the land, Thou commandest the horns to determine six days, And on the seventh day to divide the crown.” When the Sun-god on the foundation of heaven… thee,…[tablet here damaged]