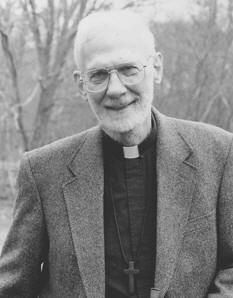

The Message of Jesus: Interview With Robert F. Capon

Robert Farrar Capon |

GCI Pastor Tim Brassell conducted an interview in 2004 with Christian author Robert Farrar Capon in the Capons’ home in Shelter Island, New York. “I was truly overwhelmed by Robert and Valerie Capon’s graciousness,” said Tim. “The morning flew by. We had lunch together, and then they invited me to return for dinner. They made me feel like we’d been friends for years.”

Here is a transcript of the interview:

Tim Brassell: Good morning, Dr. Capon. One of the topics in your new book, Genesis: the Movie, is what you referred to as biblical literalism. What is biblical literalism?

Robert Capon: Well, of course the book has a long, careful answer to that question. A short answer might be that biblical literalism is simply a mistake in the way people read the Bible. The object of Genesis: the Movie is to help people stop reading the Bible as if it were a manual of instruction in religion or spirituality or morality or anything else and to start watching it as a film, presented to you by the Holy Spirit, who is the director.

TB: What is the difference?

RC: When you watch a movie, you don’t stop 10 minutes into the film and try to decide what it means. You cannot fairly say anything about the movie until you have seen the whole movie and hold it in your mind as an entirety—as a whole piece. And that is what needs to be done with the Bible. It has to be seen as one thing. So I’d like people to see biblical inspiration, not as a matter of word-by-word inspiration, but as scenes in the movie the way the director wants to show it to you, that is, scene-by-scene.

TB: What are the pitfalls of not seeing it that way?

RC: The pitfalls are that you start teasing meanings out of things without seeing the whole picture. A simple example is that you cannot decide what the very first words in the Bible, “In the beginning,” mean until you see all the other occurrences of the image of “beginning” in the rest of the film.

In other words, you can’t properly understand that word beginning until you see Jesus, in John, say, “In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God and the Word was God.” And finally, at the end, where you have in Revelation, “I am the beginning and the end, the alpha and the omega,” and so on.

In other words, you can’t properly understand that word beginning until you see Jesus, in John, say, “In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God and the Word was God.” And finally, at the end, where you have in Revelation, “I am the beginning and the end, the alpha and the omega,” and so on.

So as the movie progresses, we find that in the beginning was Christ, the incarnate Word. You have clues woven into the movie such as, “He chose us in him before the foundations of the world.” When we see the whole picture, we can see what the director was doing with the film, what he was getting across to us, from the beginning. Before anything was made, it was all already done within the Trinity. The whole thing was accomplished before it started.

TB: Just as in Revelation 13 where it says, “the Lamb slain from the foundation of the world.”

RC: Yes, yes, yes!

TB: Is there an opposite ditch from biblical literalism?

RC: Yes. I call biblical literalism the literalism of the right. Now there is also a liberal literalism of the left. And that would be all the Bible critics who decided that you can’t take everything seriously. They see the problem with literalism, but go to the opposite ditch, as you put it. In their view you need to try to find things you think are really true and say those should be taken seriously, but the rest can be tossed away.

TB: So really, the liberal ditch is bad for the same reason.

RC: Yes, because they still don’t escape literalism. They’re still saying there is a sacred, literal original in there somewhere and they have found it by taking out stuff. But in the imagery of a movie you don’t have that—you don’t take out nothin’—you accept the film just as it is delivered. And, as with all the rules of film watching—don’t interrupt!

TB: You have characterized the judgment parables of Jesus as telling us, “Nobody is left out who wasn’t already invited.” Would you elaborate on that?

TB: You have characterized the judgment parables of Jesus as telling us, “Nobody is left out who wasn’t already invited.” Would you elaborate on that?

RC: Well, that’s what I got out of reading the judgment parables. In the way Jesus presents them, people were not denied an invitation to the party; instead, they were kicked out of a party they were already at. Even in the parable of the prodigal son, nothing was stopping the elder brother from joining the party where his younger brother was being received and honored—nothing but his own resentment. He isn’t kicked out; he refuses to go in. But that parable brilliantly ends with a standoff.

The elder brother refuses to join the party, but the father won’t leave it like that. He goes out to the elder brother, and Jesus ends the parable with the father and the elder brother standing out in the courtyard—forever—at least for 2,000 years now. And there it is. It’s all done in the presence of the redeemer. Even the obstinacy of the older brother. The father doesn’t give up. He’s right there with the elder brother, aching for him as much as he ached for the younger one, the prodigal.

TB: Does this tie in, would you say, with Romans, where Paul says, “Nothing separates us from the love of God?”

RC: Of course. It’s very hard for the human race to accept that cold: “Nothing separates us from the love of God.” We think there must be some breaking point where God would give up on us. “Well, what about if we…?”

Sin is not a problem with God. God solved all his problems with sin before the foundation of the world, in the beginning—and it’s done. The iceberg that lies under the surface of history is the Son of God; redemption is the mystery behind all history. Sin is a permanent irrelevancy. And God is the one to say, “Look, I have taken away the handwriting that was against you.”

I like the translation in Matthew, “forgive us our debts as we forgive our debtors.” What do we do when we don’t forgive somebody else’s debts, or literally, their sins? We carp on what they owe us. We look at the chits that we have saved. This is what you owe me and you haven’t given it to me. There is an IOU I hold against you, and I gotta have this…. Well, it’s not that way with God. With God, it’s done—there is no handwriting against us. It’s done. He’s not holding IOUs.

TB: So why do we have such a love affair with legalism?

TB: So why do we have such a love affair with legalism?

RC: It’s something that’s afflicted the church from the start. Humans have a hard time believing that God doesn’t hold IOUs. But Paul says the law cannot save. He says, “He has made him to be sin for us, that we might become the righteousness of God in him.”

TB: Have you found an effective way to present the gospel to a legalist?

RC: No (laughter). The reason I say no is because all that you’re going to do is present it and shock them. If you try to do it in a winsome way, which I always do, and try to do it to show them the freedom of it, then you’ve got a chance. A small chance, not a big one, but you’ve got a chance—because, when it happens—people go, “Wow!”

I was made visiting professor of something or other in religion at the University of Tulsa for the fall term back in the ’80s or ’90s. I had two classes. One was a 39-week beginning course. I taught the parables, and I had, I would say, everybody against me. All these youngsters were against me because what I was saying was against everything they had ever heard. I pounded and pounded and pounded for 39 weeks. I went through every parable.

One young lady came up to me at the end and said: “You know, when I first came here I didn’t like anything you said, because it contradicted everything I knew. But, you have done something. For the first time in my life I see that it really is good news” (laughter). They thought the gospel was bad news! That’s what legalism does to people.

TB: Can a pastor take grace too far?

RC: No. A pastor can’t take grace too far. That is, not unless he claims that sin doesn’t matter. If he claims that, he’s abusing grace, because sin does matter. It matters to me, the sinner. It matters whether I leave myself stuck in it.

Suppose a mother has a kid who comes in all muddy. She just washes off the mud. She loves her child and doesn’t wait to see whether the kid decides if he wants to live with mud all over him. She just washes it off. And if she is a faithful, true mother, she will continually take that mud into herself and say, “Well, this is my son, and I will stick with him.”

TB: Mothers are like that.

RC: Yes. The point is that sin is mud. It’s a cover-up or cover-over of your true being as a person. And Jesus has washed it away. He’s erased the sins. He’s washed them away.

Not all churches practice infant baptism, but infant baptism is a wonderful testament to absolute grace. It says, “It’s done.” It doesn’t say, after this if you do something, then you’ll be OK. It says, “You’re OK now,” not because you did something or thought something or figured something out, but you’re OK now because Jesus says so.

It isn’t religion that makes you OK with God, it’s God who does it. The sacraments are not religion. They do not cause something to happen. You don’t change the wine in the Eucharist into the blood of Christ, the presence of Christ. You just put up a sign in which you say, he is present in this sign as he is present in all things, including me.

For example, a priest in my jurisdiction holds up the bread and wine before communion and says, “Behold the Lamb of God that takes away the sins of the world.” That means that the whole world is changed, changed by Christ.

TB: Some people say that if you preach grace a lot, people will get the idea that they can go ahead and sin all they want and still be saved. What would you say about that?

TB: Some people say that if you preach grace a lot, people will get the idea that they can go ahead and sin all they want and still be saved. What would you say about that?

RC: First of all, I would say they’re perfectly free to sin all they want whether you give them permission or not. But the thing that they are not free to achieve on their own is their own forgiveness, and that is what is already done. They simply have to accept that in Jesus, God has forgiven their sins.

Jesus is the Word of God incarnate. The incarnation has been in the works from the beginning. The incarnation is from the foundation of the world—no, before the foundation of the world. The incarnation is not an afterthought. God didn’t say, “Uh-oh, I’ve got to do something now,” after Adam and Eve ate from the tree. The incarnation is built into the fabric of the creation from before time began. So after sin came into the picture, history simply becomes the restoration of the human race to God in Christ.

It’s all that and also the results of paying no attention to that restoration. You can’t experience what you don’t pay attention to. What’s the first argument that happens after the fall?

TB: Cain and Abel. They argued over religion.

RC: Exactly. My god likes my sacrifice better than your god likes your sacrifice (laughter). Adam and Eve exit the garden, and the angel guards the way to the tree of life with a flaming sword, so this brilliant idea that we will be like god blows up in their faces. And of course, the only thing that could mean is that even though they couldn’t make themselves god, they could turn God into a copy of themselves.

TB: God in their own image?

RC: Yes. First comes the idea that we will be like God, and then the next disaster is to make God like ourselves. The basis of classic orthodoxy, with all its faults, is that it does say it’s all done. It does give you the doctrine of the Trinity. Pure monotheism is dangerous. The doctrine of the Trinity embraces the paradox of mutuality in God himself without violating the unity of God—because it can only be presented as a paradox and a mystery.

RC: Yes. First comes the idea that we will be like God, and then the next disaster is to make God like ourselves. The basis of classic orthodoxy, with all its faults, is that it does say it’s all done. It does give you the doctrine of the Trinity. Pure monotheism is dangerous. The doctrine of the Trinity embraces the paradox of mutuality in God himself without violating the unity of God—because it can only be presented as a paradox and a mystery.

Paradox can take you on trips that religion can’t even buy a ticket for. God is who God is, who he reveals himself to be, not something we can reason out or come up with by some kind of logic. And from before the foundation of the world, God is both Creator and Redeemer. The incarnation of the Word stands under and upholds everything, which means we can pay attention to the restoration that is already a reality for us.

TB: How would you describe the unpardonable sin?

RC: I figure there isn’t one. Or do you mean to sin against the Holy Ghost?

TB: Yes, that’s what I mean.

RC: When you say sin against the Holy Ghost you’ve got to mean the turning of one’s back on the Holy Spirit, who takes of what is Christ’s and shows it to us. If you are unwilling to take that, to be open to what the Spirit shows about Christ, then that cuts you off automatically. It isn’t that you get punished. It means that you have blinded yourself to the Spirit’s communication to you about who Christ is for you from the foundations of the world.

TB: That reminds me of what C.S. Lewis was saying in his last Chronicles of Narnia book, The Last Battle.

RC: Yes—a wonderful book.

TB: The dwarves, they just refused to see it.

RC: That was a wonderful image. That was one of the big strokes of genius in The Last Battle.

TB: Who are some of your favorite Christian writers?

RC: Let me give you some of my history. When I was 17, it was C.S. Lewis. And then he led me, because of his kind words, to G.K. Chesterton. Read his book, Orthodoxy. It’s a wonderful book. There’s one chapter in that book called “The Ethics of Elfland.” Elfland is the land of the fairy tales and the nursery tales—and all those stories that the human race has made up, and he says something I think that applies to miracles. Miracles are not what we think they are. Apples are gold in Elfland only to refresh the forgotten moment when we first found that they were green. In Elfland the rivers run with wine, only to remind us for one wild moment that they run with water.

Creation is just as miraculous now as it was at the beginning, because redemption is present at every moment and every place throughout every part of creation. The creation and redemption are one act, not two. There is not one without the other, and it has never been otherwise from the very beginning. In the moment Adam and Eve eat of the fruit of the tree, they are redeemed. Not by that act but by him who made them. And therefore everything that happens after that is a proclamation of the gospel.

The angel with the flaming sword is a proclamation of the gospel because it says, look, in your shape I wouldn’t even think of letting you try to go back on your own. You cannot go back, you can only go forward into the mess you’ve made, but I will follow you every step of the way.

To go back to the analogy of the Bible as a movie, you see these events as a movie, and what do you think about? Well, at first it’s not clear, but you know it’s going somewhere. Then, once you see Christ on the cross and Christ risen and Paul writing about the mystery of Christ—wow! Now you know what’s been behind everything in the movie from the beginning.

That’s the reason why the greatest help in the interpretation of scripture is a concordance. And preachers are good to the extent that they have in their minds a concordance for the passages of scripture. And that’s how, for example, Augustine worked—he had it all in his head—all the scriptural references. You have to see the Bible as one complete story, with redemption in Christ as the underlying theme and plot, the whole point of the story from the first scene.

You know what’s fun? When you watch a movie, try to identify the Christ figure. I mean the figure who makes the plot work. It doesn’t even have to be a human character. It’s the one who does for the plot of that particular film what Jesus Christ does for the world. There’s a movie by Woody Allen called September. It’s about an extended family in a New England summerhouse—a wonderful luxurious summerhouse. It had been in the family for years and years.

Now, this is the most dysfunctional family you could possibly find anywhere. They’re all sniping and they’re falling apart and everything else. Since everyone is so rotten, where do you find the Christ figure? Well, what holds them all together? It’s the house. The house is the Christ figure in that movie. It was already in all their lives before the story began. It was part of their history. It was part of their formation. It was doing the work of Jesus in the terms of that story.

TB: What would you say is the most important key to interpreting the parables of Jesus?

RC: Getting the Christ character right. Who is the Christ figure in the Prodigal? The father. Who is the Christ figure in the Good Samaritan? The Samaritan. The Christ figure in the Lost Sheep is the shepherd.

And the point is that it’s not the lostness of the sheep that drives the parable—it’s the goodness of the shepherd. The shepherd loses the sheep and acts out of his own goodness to alleviate his own loss. The finding, the saving, are all in his hands—the sheep do nothing but get lost. It’s all grace.

TB: You like to cook; you’ve even taught classes and written books on cooking. Let’s say God has a favorite recipe—what would it be?

RC: It’s the recipe of creation and redemption. That is the recipe that runs through the whole Bible. The idea of coupling the New Testament with the Old and taking both seriously is to say you really don’t want to stop the recipe in the middle.

The Son of God is both the Creator and the Redeemer of his creation from the very beginning of the recipe. The perfect creation he fashions through the Spirit by the will of the Father and then hands back over to the Father is what the Bible is all about, Old and New Testaments, beginning to end. One complete and perfect recipe for a new creation, a redeemed creation, from the very start.

TB: What advice would you give American Christians today?

RC: Well, to go back to the analogy of the Bible as a movie, I would say just watch—listen and watch the film. Try to get rid of all the things that you’ve been told it’s about and just watch it unfold as it tells its own story. And never think you have to get it all nailed down and figured out. Just watch and let it tell its story to you.

RC: Well, to go back to the analogy of the Bible as a movie, I would say just watch—listen and watch the film. Try to get rid of all the things that you’ve been told it’s about and just watch it unfold as it tells its own story. And never think you have to get it all nailed down and figured out. Just watch and let it tell its story to you.

For example, Augustine was careful when he said the first chapter of Genesis is creation in the mind of God, and the second chapter is creation in time and space. He went on to say that you can take it the other way around if you want. That’s important. Remember that you can always take it the other way. In other words, I don’t have to be right about it. The film itself is genius, and we must stay in our seats and sit at its feet.

TB: What do you think the ministry focus of the American church should be today?

RC: Get people to watch the film. That’s it. And help them watch it. Help them get rid of bad watching habits. The brilliance of orthodoxy is that it does see Scripture, every bit of it, as the Word of God, the Word of God incarnate as a matter of fact. And every bit of scripture is part of the same great story, the same great recipe of creation and redemption.

TB: You’ve said that God rules by chance. Could you elaborate?

RC: To return to Genesis: the Movie, the world as it’s presented in the mind of God in chapter one of Genesis is good. Evil doesn’t show up until chapter three. Obviously, however, evil is built into the world from the beginning. When God makes the creatures of the sea, how do they live? They eat each other. When he makes the creatures of the land—same thing.

He makes the world as an ecology—it works by life and death. Death is the engine that drives life—creatures kill and eat one another to stay alive. Even plants die so that animals can live. And it has always been that way—it’s the nature of creation. Creation is an ecology of life and death, and it works! The brilliance of the ecology is that it is created purposely to operate on sheer chance, that is, creatures eat the next edible thing that they see. Foxes eat chickens and so on. All that is done within the ecology God set in place.

One of the great insights we’ve had in the last century is to recognize that we are wrecking the ecology of the world by trying to control it. You might say God runs the world like an honest casino operator—he doesn’t rig the wheels. He doesn’t stack the deck. He doesn’t interfere in the ecology of the world as he has let it unfold. Why? Because he knows the odds.

That’s how insurance companies work. They don’t influence people’s lives to keep them alive or kill them or anything else. The insurance system works because companies know the odds. In God’s case, he built in the odds from the beginning. God made a random creation by design, and he is omniscient—he knows how his creation ecology all plays together and works itself out.

So, what I say about Genesis is that chance is not the enemy of design—chance is the design. And God, in Christ, runs the world by coming into the world and being roughed up by it—by entering the rough world—by accepting the negative odds for himself. He took on himself the part of the creation that went bad, the evil part, and redeemed it by letting it play itself out on him and then being raised from the dead.

TB: Since 9/11, many have questioned God’s goodness in the face of so much evil in the world. Would you share a few of your insights on that topic?

RC: The theological term is theodicy. Theodicy is trying to defend or justify the ways of God to man. Forget it. It’s a useless pastime.

The ways of God are clear enough and they are: You can do anything that you can manage to do. It could be good. It could be bad. It could be indifferent. It could be anything. God doesn’t force people to behave. God doesn’t stop sinners from sinning—he doesn’t stop murderers from murdering. Of course, he does make exceptions, but those are exceptions, not the rule.

The wonderful thing about the ecology of good and evil, of life and death, is that death is given free reign as much as life. But from the beginning God knows the end, and the end is redemption. Redemption is the whole story from beginning to end. God took the evil on himself and redeems it—Jesus’ resurrection is the core of the whole thing—the real meaning of the whole creation. Death is swallowed up in the victory of life. It’s all about redemption.

TB: One other question. You said that you cannot discover history by finding facts?

RC: Yes. History is not lying around out there on the ground waiting for us to discover it and pick it up. History is what we make of the facts that are lying around out there, how we interpret them. History is story told by storytellers. You can’t rummage around and find the real history. That’s the mistake of biblical literalism, and it’s also the mistake of scientific literalism, which is liberal literalism of the left—it’s the same mistake.

RC: Yes. History is not lying around out there on the ground waiting for us to discover it and pick it up. History is what we make of the facts that are lying around out there, how we interpret them. History is story told by storytellers. You can’t rummage around and find the real history. That’s the mistake of biblical literalism, and it’s also the mistake of scientific literalism, which is liberal literalism of the left—it’s the same mistake.

They think it’s something objective or fixed lying out there somewhere. It isn’t, it’s only in here—in the mind. You can have one version of history, and I can have another. And we can argue about it. That’s how we function. It’s the ecology of mixed minds, mixed motives, mixed ideas. And we work it out and we slug it out and then we have a drink. (Laughter)

Editor’s note: Robert Capon died in 2013.

Author: Robert F. Capon